Prior to the First Poverty Enlightenment, the notion of poverty in Europe was not only deemed necessary to maintain a social hierarchy but also optimal. As per the mercantilists, poverty was necessary for economic development since they believed that higher wages would make workers work less; as such, exports would fall compared to imports (a country’s wealth was thought to have been measured from the trade surplus) and the nation’s gold reserves would go down, making the country lose power in the world stage. In the Victorian era, we saw a first-of-its-kind social safety net for the “deserving” poor– workhouses. Eventually, the present European welfare state started taking its current form in the late 19th century and early 20th century. In France, for instance, we saw in 1898 the laws on accidents in the workplace, a “Bismarckian” pension system (“retraites ouvrières et paysannes”) in 1910, social insurance in 1930 (predecessor of social security of 1945), and legislation on family allowances in 1932. In the UK, we saw the foundation of the NHS in 1948 which was the first free at the point of use medical care institution in any Western country.

The economic case can be made for a social safety net in the form of automatic fiscal stabilizers, while the philosophical case is rooted in contractarian humanist principles and “rights”. Nevertheless, most of those systems, including the NHS, were based on the socioeconomic status quo of colonialism where each Empire would use its colonies as “cash cows” to fund its ambitious welfare state venture.

While the current form of the European welfare state might have some positive externalities, not only is it fundamentally flawed in theory, but at the same time, it faces many existential pressures stemming from the reality of aging demographics and exorbitant government spending. To begin with, by European welfare state, we refer to universal public healthcare, public pensions, as well as a series of other policies guaranteeing a social safety net.

The basic flaw ingrained in the European welfare state (specifically in healthcare) is the illusion of financial security, which in reality is eroded by a malfunctioning state-owned monopoly coupled with coercion that, in turn, leads to the attrition of market forces and as such the creation of a larger deadweight loss than previously observed in the case of the provision of healthcare as a market failure. It is commonly said that for a decent healthcare system, you must have three things: universality, affordability, and quality. The European healthcare system is supposed to be both universal and affordable but lacks quality when compared to countries that have a lower involvement of the central government in healthcare, such as the US, Singapore, and Switzerland. The reason is that the over-involvement of government in the sector eliminates the concept of voluntary exchange between consumers and private institutions (hospitals) and as a result removes choice, making the industry less efficient.

With that said about healthcare, the other major component of the European welfare state is the public pension system. Even though politicians from most sides of the aisle know that it is a ticking time bomb, it has effectively become the third rail of European politics, as observed from the backlash of the populace to fiscally responsible and rational measures in the past. For instance, when the social democrat government in Greece tried to reform the public pension system in 2001 (probably the only fiscally responsible thing they ever attempted to do, because had it been implemented Greece would have most likely not have been in the situation it did following the 2008 crisis) and implement what is known as the “Giannitsis reforms” the country fell into turmoil; another exemplary case are French protests against Macron’s pension system reforms in 2023. The main problem in this case stems from the fact that the fertility rate in most EU countries is under 2.1 (below replacement); that is, there are aging demographics. This phenomenon is not a problem on its own, but it becomes one when understanding the nature of most European pension systems. Instead of every retiree having his own savings account, today’s employees have to shoulder the burden of paying for the retirees of today, and hopefully there will be enough employees around for the same to happen once they in turn retire. This was done due to inflation and governments not wanting to invest that money in commodities or indices to preserve its value. However, in an era of aging demographics, this system is simply not viable, it is a ticking time bomb.

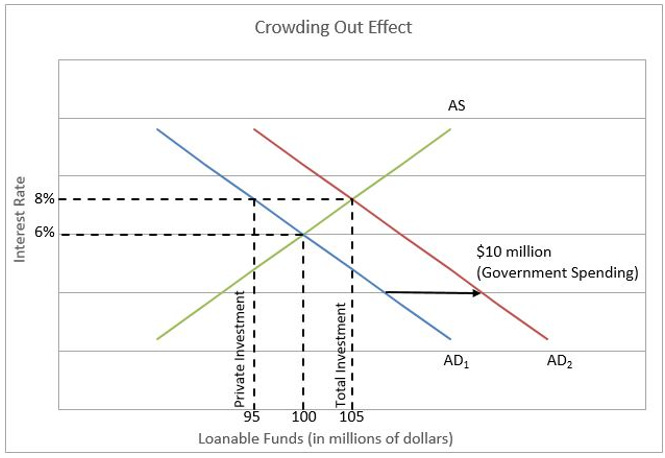

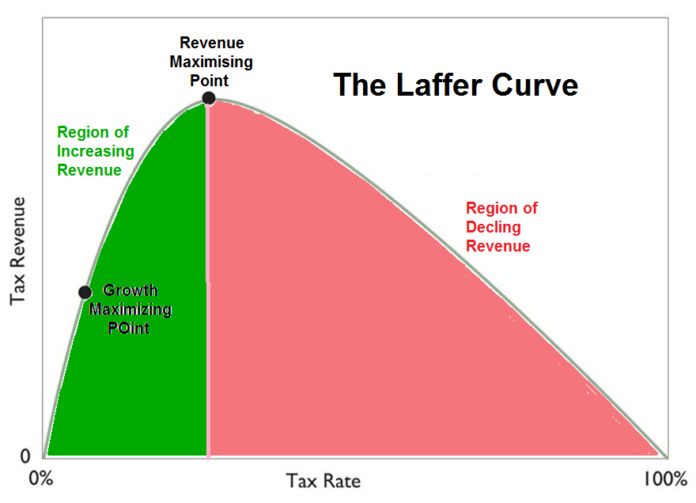

The last implication of the European welfare system that is problematic is the amount of government spending needed to sustain it. Healthcare, pensions, and safety net provisions all require money which usually comes from contributions; however, as explained above with aging demographics, when those contributions are no longer enough, the government needs to take action. The dilemma is automatically to either run a deficit or to increase taxes. The former is dangerous due to deficits crowding out private investment. When a government enacts deficit spending it pushes up long rates as they have to be borrowed in the market for loanable funds. This reduces the Net Present Value (NPV) of any stream of cash flows from private investment that is discounted by a factor that is a function of interest rates. Lower interest rates lead to a higher NPV on all private investments and boom times in the business cycle. Moreover, high deficits can cause debt vigilantes to sell a country’s bonds causing borrowing rates to go up and as such causing stagnation. On the other hand, the option of raising taxes might not only cause stagnation but could also not even lead to an increase in revenues as shown in the Laffer curve. As such, reforms may be the only viable option, as unpopular as they may be.

Figure 1 (Crowding out Effect (Higher Rock Education))

Figure 2 (The Laffer Curve (FEE.org, 2022))

When it comes to healthcare it seems like tackling the problem of coercion and as such creating a system of voluntary exchange is the only viable solution. Therefore, the reforms that could make the European health system better could focus on two areas; first, an increased involvement of the private sector as well as decentralization. That is, healthcare functions on a provincial basis (similar to the Canton system in Switzerland) where each district decides where to allocate funds instead of the central government. At the same time, minimal involvement of government is necessary to eliminate the coercive forces that undermine market forces, which is something that can happen only if public hospitals operate as Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) to ensure efficiency and universal provision under the mandatory insurance determined by the respective district. As such, a PPP system of decentralized hospitals can enable competition between districts (one district may charge higher healthcare contributions to ensure universal provision, while another might prefer more deregulation which would mean higher quality but also costs).

Furthermore, European social security would require a more radical solution since the problem is very deep. The gradual and complete elimination of the role of the state in providing pensions is necessary to ensure the survival and prosperity of European economies. The only way to do this without running a deficit is to impose a small “transition tax” while also eliminating most other safety net oriented discretionary spending. These funds would effectively be used to replace social contributions for young people in the workforce (everyone under the age of 30) who will be mandated to save their money in a pension fund.

These reforms, as unpopular as they may be, are necessary to ensure the continuing stability of the European economies against the ticking time bomb that is the current form of the European welfare state. As a result, strong political will is a must in any European Federal project to undertake these tough decisions.